Free trade and war

Avner Offer’s “The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation”

People who have read my posts in the past two years might have noticed that I discussed several times the origins of World War I (here and here and here). There are two reasons why I believe this is important. First, very few people would disagree that our world is still shaped by what happened then. Not only did the war finish off semi-feudal systems in Europe, and destroyed four empires, it set the world onto Communist, and later Fascist revolutions, and likewise to decolonization. So most of what politically exists today has its origin in 1914. The second reason is that the period which preceded World War I was a period of most complete globalization up to date, relatively free trade, and (what would be called today) neoliberal policies. Thus the similarities between that world and our own are many.

The theories of what caused the war are almost as numerous as the theories of what caused the fall of the western Roman Empire. Without going into any of them, I think they can be usefully divided into theories that stress economic factors, those that emphasize politics, and finally those that believe in accidents. For me, and I would say for most economists, it is the former (economic theories) that we are most interested in, and perhaps because of that, find most sensible. In my new book “Global inequality: a new approach for the age of globalization”, I use one of them, the Hobson-Lenin theory that sees the origin of the war in domestic maldistribution of income, struggle for foreign markets and the need to physically control the territories where the investments are made.

Avner Offer’s excellent book “The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation” (published in 1991) also provides an economic, but somewhat different, explanation. Offer’s particular take on the origins of the War may not be as well known, so let me give here a summary and interpretation.

Offer starts with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The repeal of the Corn Laws opened British agriculture to foreign competition. British agriculture could not compete, so most of the food had to be supplied from overseas. This required control of the seas. The fleet became the substitute for tariffs. Britain became richer as it "allowed" the movement of labor from less productive agriculture to industry, but its economy and society became more fragile. The navy, as Offer nicely puts it, took the role of tariff rates. While the Corn Laws existed, the tariffs made sure that there was enough food for workers; without the Corn Laws, a strong navy had to make sure the food would be shipped to Britain.

Thus, Offer implies, and at times argues, specialization and international division of labor directly led to the need for a strong military. Free trade was underwritten by arms.

But this particular calculation was not limited to Britain. As other nations started to develop, especially so Germany, they faced the same trade-off. Either Germany kept a significant share of its population on land in low productivity agriculture, or it went at full speed into manufacturing for which it needed labor to move to the cities and the food to come from elsewhere. So Germany like Britain had to make sure that it could be supplied with food and raw materials which implied also a buildup of a navy and stronger control over the agricultural neighbors who produced food, mostly in the East (Russia or what is today the Ukraine), and in the Balkans. (You can see there, if you wish, the seeds of the food driven Lebensraum doctrine, a point recently made by Timothy Snyder.)

Another element came into the picture as well. As both the British and the Germans sought to ensure the safety of their food supplies, they realized that, in the case of a war, food supply was a weakest spot for both. It was especially sensitive because neither country’s ruling class could be sure of the loyalty of its workers once the war began and food shortages spread. Socialist parties and workers’ movements, before the war, often implied as much. Either a socialist revolution or capitulation or both loomed (as indeed this eventually happened in Russia, Germany and Austria). It thus gradually dawned on both British and German military planners that the most effective way to fight the enemy was to disrupt its food supplies and the surest way to remain invulnerable was to have a navy powerful enough to repel all such attempts by the other side.

The civilian populations became the prime war target. (Offer opens the book with the ultimate effect of this strategy: hunger in Germany in the months before the Armistice and all the way to the signing of the Versailles peace treaty.) Each military advance in either UK or Germany gave only a temporary respite until the move was matched by the other side. From that point onward, it was only a matter of time and opportunity when the conflict would break out.

I will not go over the very elaborate details that Offer provides on British strategy to hit Germany at its (if I can use this dubious pun) “soft belly” (food supplies). It ranged from naval blockade of North German and Belgian and Dutch ports to land invasion of Northern Germany. The planning took place between 1905 and 1914 but the facts were not revealed until the 1960s because they would have fallen under the rubric of preparations for an aggressive war, which the Allies, at Versailles, claimed only Germany did before the war.

There is here one very important point to notice for the economists. Unlike those who (somewhat wrongly) interpreted Ivan Bloch and Norman Angell to have believed that increasing interaction and economic links between the countries would make the war unthinkable, Offer implicitly argues the very opposite. It is precisely the decision to specialize in the production of manufactures (that is, to produce something for which Britain or Germany possessed comparative advantage) that led to the need to have a war machine and ultimately to the war itself: "the adjustment to economic specialization was the root cause of the war" (p. 327). World War I was in effect the first war of globalization.

While international division of labor makes the costs of wars exorbitant for all participants, it also requires, in order that the system be maintained, a permanent armed underpinning. But that permanent armed underpinning by itself renders the war more likely because it leads more than one power to make the same calculation and come to the same conclusions. If we were to replace Britain and Germany from Offer’s book by US and China today we would not be very much remiss.

More diversified, less autarkic, countries become much more productive but at the cost of being more fragile and brittle to any disruption. Our very sophisticated economic system can be brought to a complete halt by (say) one month breakdown of all electronic communications. In 1926, Vladimir Mayakovski, after spending some time in New York, wrote this:

“Exactly under Wall Street runs a metro tunnel. What would happen if it were filled with dynamite and the entire street were to blow up and disappear into the thin air? Gone too would be the registers of deposits, titles and serial numbers of innumerable shares, and the columns of data on foreign debt.” (America, Gallo Nero Publishing, Madrid, 2011, p. 120).

Mayakovski was as far from being an economist as every poet is but sometimes poets can see better into the future than economists.

Finally, I would like to mention three excellent chapters in Offer’s book on the opposition to Asian migration into Canada, US, Australia and New Zealand. They bring, very timely, all the themes with which we are familiar today: the anti-immigrant attitude of the (White) working class which saw in Asian labor a competitor against which they were bound to lose, the rise of populist politicians, inconsistent racial stereotyping (Asian were attacked both because they were “inferior” to European migrants, but also because they were “superior”, smarter and more hard-working), seizure of would-be migrants’ assets (called then the “landing fees” that Indian and Chinese workers had to pay upon entry into Canada and the US), and finally outright ban of Asian migration. Yet one additional reason not only to read the book but to reflect on how the pre-1914 period is so scarily similar to our own.

The Germans banked on a quick end to the war, as per 1871, captured in the Schlieffen plan. Food shortages caused by a blockage wouldn't be an issue because the war was supposed to be over before they could take effect.

The need for a quick win against France was driven by the need to pivot troops to fight Russia, and avoid a two-front war, not the need to avoid a blockade. The Germans seem to have thought the British might not even enter a war with France, and indeed they did so quite unwillingly (by my reading of "The Guns of August" by B. Tuchman.)

The German violation of Belgian neutrality was the core of the Schlieffen plan, which opted for a wide flanking maneuver. This was deemed essential to a quick victory. And yet violating Belgian neutrality is what brought Britain into the war and brought on the blockade. I can't imagine their main concern was a blockade given they did the one thing committed to paper that would bring the British into the war and bring on a blockade.

Indeed, the German Navy did not feature in the Schlieffen plan at all, and was kept in port with the exception of battle cruisers and other fleet elements based in the Mediterranean and Pacific. Fleet movements required the approval of the Kaiser himself, who didn't want to risk his prestige Navy and opted for the Mahan doctrine of a "fleet in being". Submarine warfare was only adopted later in response to stalemate on land.

I think it is more plausible that the German fleet was a prestige fleet, and not one intended to protect maritime supply lines.

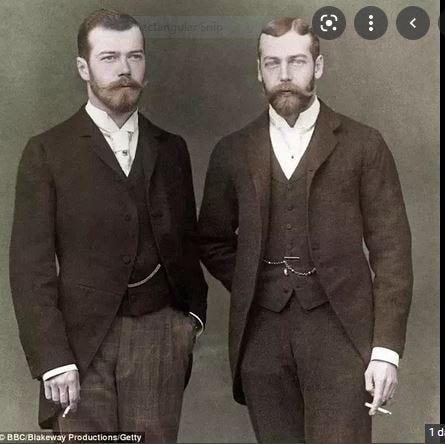

Nicholas: You add a refreshing twist (perspective) to how we might read modern history turning on the revolutions of the Great War era - in this review. I like too, the return to The mid-19th century Corn Laws - and later competition between the cousins - England/Britain and Germany.

The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations (Hanihara's Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930) Palgrave Macmillan 2016 - by Misuzu Hanihara CHOW (former Dept Head at UoMacquarie) and Kiyofuku CHUMA (first edition in Japanese 2011 - the revised/expanded version in English by 2016 - an examination of the anti-Asian (Chinese/Japanese) mood of Woodrow WILSON (including how both the UK and the US stood back allowing Billy HUGHES to take the opprobrium for his anti-Japanese stance at the Versailles Peace Treaty while giving him off-stage encouragement... CHOW's grand-father was a Japanese Embassy secretary pre-War - later post-war Ambassador to Washington D.C. Adds something, I think...