When I had a discussion with Alex Hochuli and Philip Cunliffe at their podcast (you can listen to it here), they mentioned one of my pieces on what I called the paleo-left. In the podcast, I went over the main features of the paleo-left, and I think that it may be useful to put them down again in writing. And hopefully to show that they can be readily made into actionable policies and are not just a set of nice words strung together.

The paleo-left agenda, in my opinion, has four key planks: it is pro-growth, pro-equality, for freedom of speech and association, and for international equality. Let me explain each.

Being in favor of growth means that the paleo-left acknowledges that income and wealth are indispensable conditions for human self-realization and freedom. We cannot achieve our potential, nor enjoy other non-pecuniary activities unless we have enough income not to worry where the next meal comes from or where we are going to sleep the next night. The paleo-left is against the constant denigration of growth because it recognizes that for an ordinary person improved material conditions of living open the “realm of freedom”: we do not want households where mothers have to wash clothes in the nearby creek or in the bathtub; we want households with washing machines. (Of course, for people who already own washing machines this might seem like a trivial demand. But for half the world that does not it is not trivial at all.)

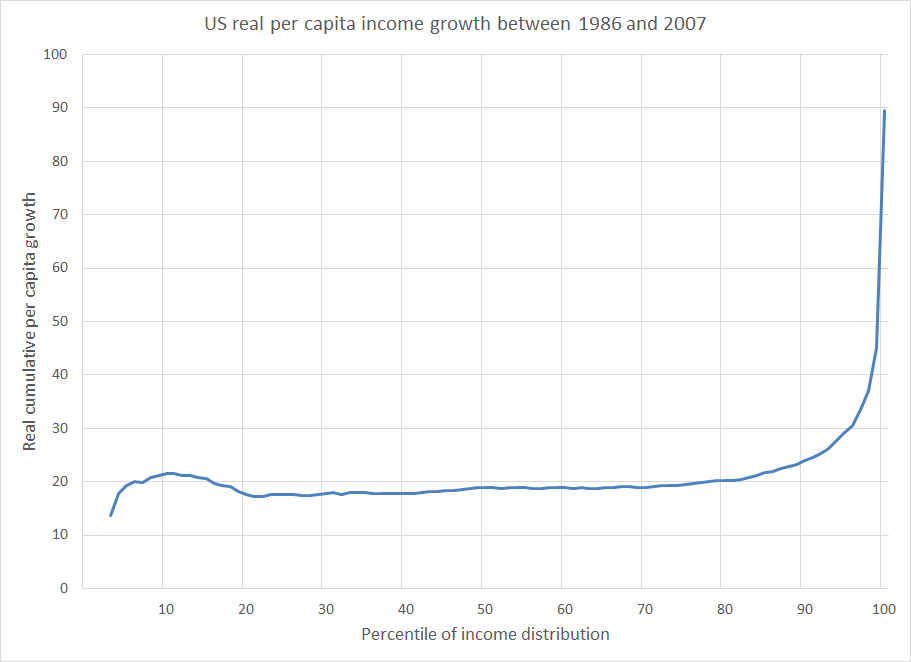

Growth as such without taking into account who benefits from it is neither ethically acceptable, nor politically sustainable. That’s where the second plank comes in: economic equality. Growth cannot be blind, nor can it be such that most of it, like in the US in the period 1986-2007 (see the graph below) is collected by the rich. It must be pro-poor which means that incomes of the lower groups should rise, in percentage terms, at least as much as incomes of the richer groups. How to achieve this? Not only through direct taxation or indirect taxation of activities and goods consumed by the rich (the latter is an area which is, in my opinion, under-utilized). It can be achieved through high inheritance taxes which would ensure reasonably equal starting position regardless of parental wealth, by almost free or fully free public education and health, and by special support for the young, around the time of their first jobs. The young are now in the developed Western societies as a group in need of as much support as what people who are currently old managed to politically achieve in the 1960s and 1970s.

Reduced income and wealth inequalities are both an objective in themselves and a tool for achieving something else: relative political equality. That equality is undermined in today’s advanced societies not, as it is claimed, by an ill-defined “populism”, but by a very opposite danger: that of plutocracy. The fact that rich people fund the campaigns, pay politicians (which is just a more subtle form of bribery), and control most of the mainstream media, makes mockery of political equality.

The paleo-left should, in my view, eschew such terms that the neoliberal discourse has captured and made meaningless, like democracy. We have to acknowledge that the term “democracy” has been hijacked by the neoliberal plutocracy in the same way that the term “people” was hijacked by the communist authorities in Eastern Europe. Both terms are used to cover up the reality.

Instead the paleo-left should focus on something much more real and measurable: approximate political equality. The latter implies public financing of political campaigns, limits (or bans) on rich people’s control of the mass media (no “Washington Post” ownership for Jeff Bezos), and equal participation in the electoral process which in turn means making participation in the elections easier for hard-working people. Current elections in the US are intentionally scheduled for a working day, and it is neither a surprise, not an advertisement for “democracy”, that even in the most important elections one-half of the electorate simply does not participate.

The paleo-left also recognizes that the freedoms of speech and association are largely meaningless so long as approximate political equality does not exist. Individuals can spend hours and days arguing on Twitter, but it will carry zero political influence as compared to well-paid and organized think-tanks and other institutions whose objective is to directly affect policy. It is in that area that a vague use of the term “democracy” in reality conceals vast inequality in access to political power.

The last plank is internationalism. This is, of course, an old left-wing slogan, and it should not be seen as something that is just tacked on to the rest of the domestic agenda. It is a constituent part of the overall agenda. The paleo-left accepts that different countries and cultures may have different ways in which they choose their governments or in which they define political legitimacy. The paleo-left is not ideologically hegemonic. The paleo-left might believe (and should believe) that its own approach is the best, and is right to argue for it, but the argument must be always at the level of ideas, must avoid gross interferences in the internal affairs of other countries, and must obviously never use violence. The paleo-left must get rid of the noxious idea of a “liberal world order” which is either meaningless (as it changes depending on what is politically convenient for its proponents) or is an outright invitation to wage wars. It replaces it by the respect of international law as defined by the United Nations, and by other institutions that are inclusive of all peoples. The paleo-left proselytism is made only by non-violent means, and with respect for other cultures and states, and with no coercion of any kind.

There are many other issues that cannot be directly covered by these simple rules. They concern migration, gender and racial equality, relations between the church and the state etc. but they can be, I believe, relatively easily deduced from these four general principles.

Love this, thanks Branko!

By the way- since you mention the arguments against degrowthers (which I think are valid) in the above, and you've also spoken before about their reliance on magical thinking, I was wondering what your thoughts were on what I would consider their opposite, 'green growthers'?

By this I mean those who believe in the possibility of having continued growth without any of the ecological consequences that normally come with economic expansion.

From my perspective it seems like they are as equally guilty of magical thinking as the degrowthers, because while relative decoupling is definitely feasible, absolute decoupling just is not- to invoke a cliche, there is no such thing as a free lunch, so if the economy grows, it has to be costing something in resource terms. It seems like a case of 'jokers to the left and jokers to the right'!

Thanks again! I am just about to start my phd studies and hopefully my journey as an academic- if I can one day write a book half as good as capitalism alone I will count myself very happy!

Very important question posed. It is much more complex than it seems.

But the short answer is that this "paleo-left" is utopian. I'll use philosopher István Mészáros' "Beyond Leviathan" (a book I highly recommend everybody here to read) to explain why this is, scientifically and logically, the case.

The main problem with this paleo-left is what I like to call "middle class fallacy", which exists since Aristotle and reached its most mature form in Rousseau.

The "middle class fallacy" arises from the presupposition that every political system is just and stable if the vast majority (or, in the limit, all of them) of its citizens have equal share of power and wealth (therefore, property). This is a fallacy because, as in Nature, form also follows function in Society.

Let me simplify the problem with some illustrative examples: take a middle class family from the apex of capitalism, that is, somewhere in a First World country during the post-war miracle (1945-1975). Take all of the concrete emblems of the middle class: you have a plethora of durable goods, foods and services and must be in place all the time in order for this middle class family to exist.

It is evident, in this case, that the sum of all of these goods and services must all fall into this family's budget (i.e. wage), and that, therefore, this budget must be greater, on average, than the wages of the ones who give those goods and services. For example, in order to be middle class, you have to be able to go to the supermarket frequently; this supermarket will have to have a cashier and someone who cleans the floor of said supermarket. This personnel, in order to constantly serve the middle class, must not be middle class, but instead be part of an inferior class, which receives lower wages (thus giving goods that fit on the middle class member's budget).

Sure, there are some service providers who are middle class themselves and serve middle class members who receive less than them, but they must be, on a social scale, the minority, since their wages are greater than the wages of their clients; it becomes patent that a middle class member can only serve clients of lesser wage if he has many of them, therefore the middle class must always exist in a class society (pyramidal scheme).

With the development of the middle class, a middle class culture automatically arises. With this culture, many habits and economic infrastructure which are associated with middle class culture are established - that some disappear and some ossify is immaterial to this question, as it is the social reproduction of the class that is essential. Such social structure implies the existence of inferior and more numerous classes.

Progressive taxation doesn't change this one inch; the very definition of progressive taxation already presupposes the preexistence of an unequal and socially necessary relation of production, i.e. economic system. The most it can do is to alleviate the tensions of class struggle, but never to eliminate it. Taxation is the privilege that emanates from the monopoly of violence (imperium) of the State; it can never alter the mode of production, although it can bend and/or destroy culture; in such case, the State could destroy a middle class culture, but never the concept of middle class culture.

A given middle class presupposes a middle class culture, which presupposes an economy that perpetuates this middle class culture, which is, as we have seen, necessarily unequal and unjust. The fallacy of the paleo-left is that the lifestyle of the middle class is universal, but it is not and must be not, and will never be universal. The very act of driving to a department store in order to by a washing machine already presupposes a class society, therefore structural inequality. The middle class lifestyle is not universal, therefore is historically specific, therefore it is economically unsustainable.

Just make an exercise if you're middle class: imagine if you had to pay for your needs a price that would make every one of your servants equal to you, i.e. middle class (e.g. you have to pay your plumber, delivery man, cashier, janitor, waiter, trash collector, etc. etc. a middle class price). Imagine how much the price would rise. Now imagine the indignation that would take over you, as you protest your government for "higher prices" or "lower purchase power". In order for a middle class person to enjoy a middle class lifestyle, therefore have a middle class identity, he or she has to have a mass of people from a lower class to serve him or her constantly and perpetually.

Now, imagine all of those lower working classes jobs are automated, so nobody has to do such jobs. In that case, there would be no middle class, which annihilates the problem. There would be no "approximate political equality", because there would not be any gradation of class. There would be thus no paleo-left because the end of middle class culture implies in the end of the middle class. That's why you cannot have, logically, equality and any lower inequality at the same time, which makes the proposition that "incomes of the lower groups should rise, in percentage terms, at least as much as incomes of the richer groups" a logical fallacy in this context.