June 3, 1968 was a beautiful late Spring day in Belgrade. The school year was just about to end, and, for me the best days were about to begin: until the mid-July when many of my friends who had either relatives in the village or second homes on the seaside would go on vacation and I would not see them for two months. But now, during the beautiful, clear June days with long sweet evenings we could stay out in the streets seemingly forever, play soccer, tell tall stories and talk about the girls.

During that day, June 3rd, just for a few moments, probably to pick another soccer ball, we went to the apartment of one my friends; only his grandmother was there. The phone rang. His mother called. She worked for the federal government whose HQs were across the river. In deep panic she called to tell her son, my friend, not to go out in the streets, but to stay at home because (and I do remember her words well) “the students are out trying to overthrow the government”.

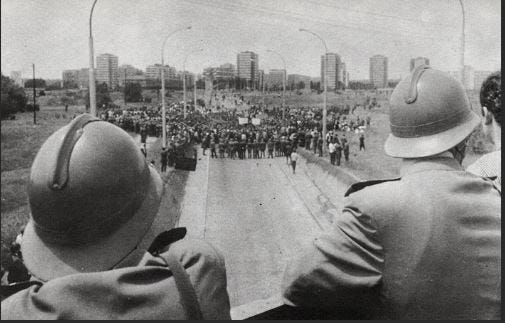

For sure, as soon as we were told by the grandmother that we should stay indoor, we promptly went outside. My friend’s apartment, like mine, was close to one of the main university buildings in Belgrade. When we, kids, got there it was already occupied by students, surrounded by the police that did not let anyone get into the university perimeter (in those days, the old-fashioned rules of the “university autonomy” were still observed, even under communism), and we could just look at the seemingly feverish activity inside and listen to the incendiary speeches carried on loudspeakers.

We were attracted to the “forbidden” things happening there. So I remember when several days later as the insurrectionist students communicated with the city only through large banners, I first saw the words “Down with the Red Bourgeoisie”. It was a new term. The students were protesting against corruption, income inequality, lack of employment opportunities. They renamed the university of Belgrade, “The Red University Karl Marx”. It was very difficult for an officially Marxist-inspired government to deal with them. The days of uncertainty ensued: the newspapers attacked them for destroying public property and “disorderly conduct”, but rebellious students continued skirmishes with the police, and proudly displayed the name of their new university. I remember vividly a bearded student with a big badge “The Red University Karl Marx” standing in the bus, and everyone around him feeling slightly uncomfortable, not sure whether to congratulate him or curse him.

But the slogan was true. It was a protest against the red bourgeoisie, the new ruling class in Eastern Europe. It was a heterogeneous class: some came, especially so in the underdeveloped countries like Serbia, from very rich families; others from the educated middle class, many from workers’ and peasants’ families. Their background was similar to the background of students who were protesting against them now.. Had the students won in 1968, they would have become the new red bourgeoisie.

The red bourgeoisie itself was the product of huge inequities of underdeveloped capitalist societies. From my mother, who got the story from my father (who came from an impoverished merchant family), I learned that on the last day of his high-school, when he managed to save enough money by giving private math classes to the rich parents’ kids, and proudly came to school in his new coat, one of the rich kids took the inkpot and poured it on my father’s jacket: “you will never wear what we wear”. Many years later when I told the story to my North European friend, he said to me: “this is the European class system in a nutshell”.

It is against such a system that that the students in the 1930s who were later to become the red bourgeoisie stood up. But by 1968 they were the new ruling class and the new students stood up against them.

This ruling class is insufficiently studied and known. It varied between the countries. I liked a book by Tereza Toranska about the new bourgeoisie in Poland, entitled “Them”; a young Serbian journalist Milomir Maric wrote in the 1980s a popular book called “The children of communism” (in the origin “Deca komunizma”). The story of the red bourgeoisie’s very top is narrated in the Russian novel, “The house of government” by Yuri Slezkine. One can find it in Solzhenitsyn’s “First Circle” too. Emma Goldman noticed it very early on, just a few years after the October Revolution. I was pleased to re-discover that I discussed some of its empirics (income level, housing ownership) in my 1987 dissertation. But this is all very little. The class is unexplored, neither in literary terms nor in its economics.

Like all ruling classes, its members did not think they were a ruling class. I asked many years later one of my close friends who, thanks to her belonging to the upper echelons of the red bourgeoisie, spent several summer holidays on the three small islands off the Dalmatian coast that Tito took for his exclusive resort, how were social relations among the people there: powerful indeed, but each with their own different agendas, wives, children, preferences, drinking habits, and the like. (Very similar to the US Martha’s Vineyard in the Summer: people who may not suffer each other politically, but are “condemned” to be there together, sharing the same beaches, restaurants, tennis courts, with children fighting each other or falling in love.) She told me nothing: she saw none of the political infighting or personal feuds reflected on the beaches or in the altercations over the umbrellas. She did not think people there were special in any way. It was just another workers’ rest home, with better food and more comfortable rooms.

The Yugoslav red bourgeoisie was perhaps specific because it was self-created (i.e. came to power by itself), and developed among its members a feeling of pride connected with non-alignment policies and the oversized role that Yugoslavia, compared to its objective importance, played in the world. Eventually, that bourgeoisie splintered along the republican lines, every one deciding that it would be more powerful if it could break country into smaller pieces and rule that small piece unmolested by others. That’s how democracy was born.

I thought of that recently—as indeed I had for many years—as I read about the background of many among the capitalist rulers of Yeltsin’s Russia and today’s Putinism. Their origins are typically in the affluent upper-middle class of the red bourgeoise. That ensured for them all the privileges of the Soviet system, including (in the Soviet case) the ability to travel to the West, to trade in foreign currencies, to listen to the latest rock albums from England. They were the ones who, when Gorbachev came to power, most eagerly embraced “democracy”, adulation of the United States, and gaily participated, with Western support, in the plunder of the country. They bought villas in the Riviera, and then, either disappointed at the treatment they received in their Summer resorts by their new Western neighbors, or having overgrown their infatuation with the things Western and the United States in particular, moved to the other side, championing nationalism not only as a way to stay in power, but to create an ersatz ideology that would justify their continued rule.

How similar our experiences are. Yours in Belgrade, mine in New York City in April and May of the same year at Columbia University. Some of the specifics are different, but the base is the same. We, like others in cities around the world, were protestng against the unfillfileed promises of our country's leaders, the ideals they supposedly espoused, in some contained in founding documents. In my case, after participating in the protests, I dropped out of Columbia. The real world beckoned with such force I could no longer remain in what to me was a world of theory, much of it hypocrictical, not the reality of experience. It was a good decision. I learned much more than I would have if I'd stayed. Your great work, based on emprical evidence, which exposes the contradictions we saw in 1968's spring and much more, is a testament to this. As always, thank you.

China's governing elite has not been based on wealth based or inheritance for 1500 years.

It has gradually reduced the proportion of officials with relatives in government from 63% in 600 AD to 6%-7% today. Those who get in endure a 25-year trial by ordeal, as has been the case for a millennium.