The long NEP, China and Xi

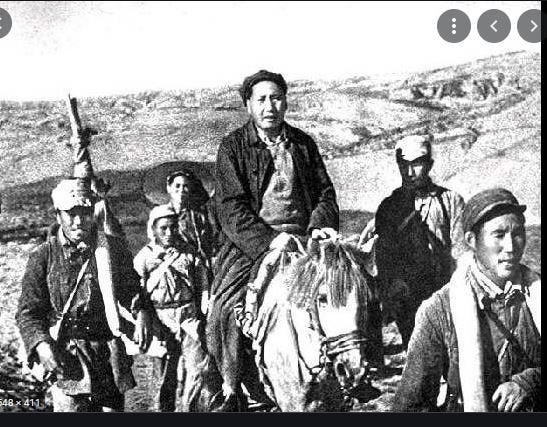

From the Long March to the Long NEP?

Many journalists, commentators and political scientists see the recent policy changes in China as “the return to communism”. They in particular point out to a number of measures whose objective was to limit lending by internet companies, to ban for-profit tutoring, and to put a squeeze on companies producing internet games (the latter were, tellingly and ominously, likened to “the spreaders of the spiritual opium among the Chinese youth”). Western commentators are shocked by Chinese government’s apparent indifference to what such measures might do to the stock markets in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong. (In effect, they have all declined during the last month). This is in signal contrast with government’s concern, and even panic, when the Chinese stock market went through severe turbulence in the Summer of 2015.

The commentators “transfer” or impute to China their own ideological biases. That bias consists in an excessive focus on the stock markets as almost sole indicators of an economy’s health. This of course is not surprising in a country, like the US, where 93% of financial assets are held by 10% of the population (see E Wolff, A Century of Wealth in America). The latter are also the richest people and consequently things that affect them will be –given that they control the media either directly (as Bloomberg) or indirectly, because they are the main buyers of the news—reported much more extensively than things that affect the other 90% of the population. All of this makes the stock market acquire an hypertrophied importance compared to what is its real worth. It gives us though an excellent insight into who really controls social and economic life of a country.

Donald Trump was merely an extreme example of the ruling class’s singular (and fully reasonable, from the point of view of their financial interests) obsession with the stock market. Trump decided on his policy moves, not merely domestic but even foreign, in function of their effect on the stock market. One might recall that Thump’s only reason for not allowing infected patients to disembark from a ship in the waters off Long Beach in March 2020 was not to spook the stock market. (Little did he—and all of us with him—know what will happen next.)

Let me give you a personal story that encapsulates the importance of the stock market for the rich. In August 1991, I was on vacation in Martha’s Vineyard, the island rightly known as the abode of very rich democrats. (The most recent house owner there is Barack Obama.) The vacation coincided with the anti-Gorbachev coup in Moscow (August 19-22). So everybody, in that small enclave where I was, rushed in the morning to watch TV news (these were the years before the Internet and smart phones). Absolutely dramatic events, with global and historical consequences, were unfolding in Moscow: the coup leaders were giving a badly-organized press conference, the army had seized main buildings in Moscow, demonstrators began to descend in the streets, Yeltsin seized the Russian Parliament building, it was unclear if Gorbachev was arrested or not….One was watching history happening in front of our own eyes. But after about half-an-hour of live coverage from Moscow, the liberal elite decided that it was enough, and switched the channels: they tuned in on the New York Stock Exchange, and most attentively watched the developments there mentally calculating how good (or bad) were the events in Moscow for their portfolios. Some of us who were more interested in the fate of the Soviet Union, communism and the world than in stock quotations were in the minority, and we had to divine the events in Moscow from the gyrations of the stocks in New York’s bourse.

China wants to be different. In a society of political capitalism, as I argued in Capitalism, Alone, the state tries to maintain its autonomy. In the United States, the state acts as a custodian of the capitalist interest “managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie.” In political capitalism, though, the state must not allow to co-opt or to be “contaminated” by capitalist interest. In other words, capitalist interest is one of the interests to consider—but not the only one, or even perhaps not the chief one.

This approach is consistent with the long Chinese tradition of the state keeping merchant and capitalist interests at arm’s length. Ho-fung Hung, for example, nicely describes how Qing bureaucracy sided in industrial disputes with workers, and not with “masters” as was commonly the case in the nineteenth century Britain (my review). The same arguments were made by Giovanni Arrighi (reviewed here), Jacques Gernet (on Southern Song China), Kenneth Pomeranz (reviewed here), and Martin Jacques (reviewed here).

Furthermore, if one looks at the current Xi-led party from a Leninist perspective (which Xi may not be loath to do), the same conclusion is reinforced. The Chinese capitalism may be seen as one “long NEP”—which might last a century or even two--wherein capitalists are given free hand in practically all areas of economics, but the commanding heights of the economy are preserved for the state (which means they are under CPC’s control) and the political power is not shared with anyone, least of all with capitalists. Thus the state maintains freedom of action vis-à-vis socially the most powerful group (capitalists), and can ignore their complaints when an overarching social interest is at stake; as in the three examples of regulatory and legal crackdown was arguably the case.

Can the autonomy of the state end, and will bourgeoisie take over the Chinese state as it did in the West? It is quite possible. The modernization theory argues that. There are, I think, three ways in which it could happen.

First, there could be a middle-class or bourgeois revolution. It should be noted however that no revolution against communist regime had ever succeeded. The one that came closest was the Hungarian revolution in 1956, but it was crushed externally, by Soviet arms. So that possibility, so long as the Party-state is united is, I think, extremely unlikely.

The second possibility is “Gorbachevization.” This means that the top echelons of the party move towards social-democracy. This ideologically makes lots of sense given that originally communists were part of social-democracy. So the ideological gap between the two is not very wide. The end of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union came when several communist parties, became, either at the top (like CPSU) or throughout its membership social-democratic. The latter was the case, by 1988-88, for at least the Hungarian, Polish and Slovenian communist parties. They came close to the Italian CP, ideologically and politically.

The third possibility is “Jiang Zeminism” whereby the party increasingly accepts among its top members capitalists, and reflects their interests. In a recent paper in the British Journal of Sociology Yang, Novokmet and Milanovic find indeed that while CPC membership (by the end of Jiang Zemin’s rule) was more similar to the overall composition of China’s urban population than before, the top (richest) CPC members were increasingly diverging from the rest of the membership and the population. Here is our conclusion: “While the structure of CPC membership in the recent period approximates better the population structure than in 1988, the CPC top is moving further away from both CPC overall membership structure and that of the urban population as a whole” (see here).

The “insinuation” of the rich into the top party ranks was rationalized by Jiang Zemin under the ideology of “the three represents”. One does not hear much about “the three represents” nowadays (it seems to have been replaced by Xi Jinping Thought) so that path to change is currently being blocked.

The future will tell us if in one of these three ways the Chinese state gets taken over by the rich, or not—that is, whether it remains autonomous in its decision-making.

As Prof Dikötter properly understood when speaking to a senior Party member during his research, after Mao's injustices to the Chinese people, after the murder, the torture, the denouncements, the destruction of people's lives what was the singular lesson the Party learnt - they were wrong to do so? The people count? No more Horror?

"From the point of view of a party member, what happened in 1966–67 is that Mao allowed ordinary people to criticise members of the Communist Party of China — and you should never, ever repeat that mistake." I am revolted by your almost clinical description, your doctrinaire, orthodox approach to the CPC. No one here is any the less appalled, revolted by what the USA has done to others and itself. Yet, if you and us can see clearly what the US is, indeed what the West is, why not China.

No comment is made qualitatively about the CPC leadership. Xi Jinping is believed by some to be corrupt to the tune of at least a billion USD and how many deaths, imprisonment has his purges resulted wherein such purges are only for his political survivability. The CPC is an entity of and for its own accord. The people of China have no bearing on the CPC other than a means to an end of the CPC's own interest. It appears you make a doctrinaire defence of the CPC's Marxist role but not with any perspective let alone of the consequences outside that. It is too often the reduction of, Western failings justify Chinese actions - irrespective of the consequences to the Chinese people. The outcome here, as if there is no room for America bad, China good, is that China, Russia, UK, Germany almost every nation is 'bad.' Why can't one hold all such nations as a mutually compatible understanding. Of course such a reduction has baby and the bathwater meeting the same disposable utility but the same focus on American failings must be held on China's failings. With even the economic growth and success of China we can dismiss Deidre McCloskey's Great Enrichment as a by-product of the CPC's quest for power.

"China wants to be different."

You are conflating the will of the Chinese people with the will of a dictator.