The book of the dead

Victor Serge’s Notebooks 1936-47

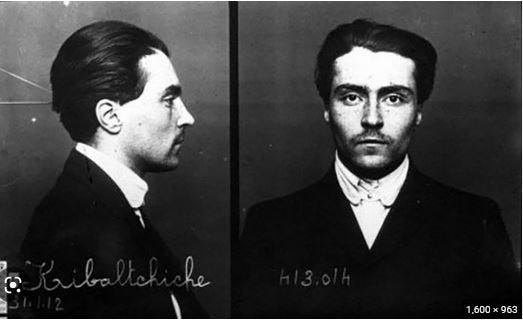

Born to Russian anti-Czarist emigrés in Belgium in 1890 => engaged in revolutionary anarchist activity as a teenager in France => condemned to five years in jail at 17 => expelled to Spain => exchanged for French soldiers held by the Bolsheviks in 1919 => joined the Bolsheviks => participated in the Civil War and worked for the Comintern => joined the Left Opposition after Kronstadt rebellion => arrested, imprisoned in Lublianka in 1928 => released => member of the Trotskyist opposition => arrested again in 1933 and exiled to Siberia => released after international protests and sent to France in 1936 => joined POUM and fought in Spain => fled to France after Franco’s victory => left France on a refugee boat to Mexico in 1941 => engaged in Trotskyist activities in Mexico=> died in 1947.

How does that look for a biography? Incredible, one could say. But not an unusual one for the people among whom Serge moved and lived. His Notebooks, not written for publication and discovered only in the 21st century, are a compelling mixture of historical reminiscences, reflections on Marxism and psychoanalysis, attacks on Stalinist totalitarianism (the term is often used), defense of democratic socialism, descriptions of Mexico, literary criticism, and art history. Most entries are mid-size, between one to three pages. They can be read separately although chronology is important, as we see how Serge’s own thinking evolves with the war that he is observing from faraway, in Mexico.

The entire Who Is Who of the artistic and revolutionary world of continental Europe is included in these notes. There is, it seems, no significant revolutionary nor writer or painter whom Serge has not met during the forty years of febrile activity. Of the leaders of the Russian revolution, Serge was the closest to Trotsky. Not all the time though. He joined the Left Opposition after Kronstadt—but the attack on rebellious sailors was led by no other than Trotsky. Nor did Serge later agree with the formation of the Fourth International. Still in the Soviet Union he was jailed as a Trotskyist and in Spain he worked with POUM, the Trotskyist militia. He arrived in Mexico after Trotsky’s assassination. Serge’s descriptions of the “tomb” of Coyoácan, the compound where Trotsky lived and was murdered, the utter desolation of the house which still had armed guards and gun turrets, with Natalia, Trotsky’s widow, emaciated, forlorn, children killed, utterly alone, are among the most poignant parts of the Notebooks.

The swirling activity around Trotsky, even after his death, is described. Serge (we do not know how) managed to meet in jail –where he is given royal treatment—Trotsky’s assassin. Here is a part of Ramón Mercader’s (whose identity was then not known) description: “Tall, well-built, vigorous, supple, even athletic. Thick-necked…a strong, well-formed head. A man with animal vigor. A fleeing gaze, sometimes hard and revealing. His features are sharp, fleshy, vigorous. Very well dressed; coffee-colored leather jacket; expensive. Under it a silk sport short, fashionable, khaki. Khaki gabardine slacks with a sharp crease; yellow shoes; good soles.”

The freres enemies, Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, are present throughout the book: the first, the co-organizer of the unsuccessful assassination of Trotsky who then fled to Chile thanks to Pablo Neruda; the second, Trotsky’s inconsistent defender; both “reunited” in the Mexican Communist Party that Diego Rivera joined after the war on the wave of pro-Stalinist enthusiasm that swept the word after the Soviet victory over the Nazi Germany.

The Comintern’s Who is Who (Willi Mūnzenberg, Franz Mehring, Otto Rūhle, Anton Pannekoek) is accompanied by the Russian and continental European intellectual elite: Ossip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Maxim Gorky, Boris Pasternak, Aleksei Tolstoy, André Breton, André Gide, Antoine de Saint Exupéry, Romain Rolland, Stefan Zweig, Pablo Picasso. Each of them is, often in passing, sketched in a few paragraphs: Aleksei Tolstoy, the kindly count who gives fabulous parties while famine rages and is chauffeured in Stalin’s private car; Anna Akhmatova “her enormous brown eyes in the face of an emaciated child”; André Gide in search of popularity, complaining of Malraux trying to upstage him, yet with sufficient intellectual honesty to write “Le retour de l’URSS”; Romain Rolland, to whom Serge owed his release from Siberian exile but who gradually moves to a pro-Stalinist position and refuses to condemn the Moscow Trials; the sky- high vanity of André Breton, “a personality that is nothing but a pose”; the petty-bourgeois Stefan Zweig; Picasso painting for “art galleries catering to bourgeois collectors fed on intellectual refuse.”

It is a book of the dead. In an orgy of ideologically-inspired killings that engulfed Europe, those who were not killed by Stalin, were killed by Hitler, and those who have survived both, were either killed in wars or committed suicide. Almost no one died in his or her bed.

How about politics? Serge does not present a coherent view of it, nor can one expect this in a diary. He sees the world as composed of four political forces: conservative capitalist, Stalinist, democratic socialist and fascist. The defeat in the War seems to have eliminated fascism. The fate of Europe and the world depends on the interaction of the remaining three. Capitalism is ideologically bankrupt and the development of technology requires planning. So, it is doomed. Stalinism is ascendent. It destroys human freedom and human soul and has besmirched all the communist ideals. It needs to be opposed at all costs; intransigently. Democratic socialism is, Serge believes, the only humane alternative, but can it win as Stalin is poised to conquer half of Europe? (Serge was right on that even if he was often wrong in a number of predictions made while the war was going on). Like with every contemporary observer and participant in thus struggle, we are left with possibilities. No one knows which one will turn out to be right.

The essential dilemmas and the main forces that shaped the post-War are nevertheless described with remarkable prescience. If we consider the period 1945-1990, it can indeed be described as the struggle between these three ideologies which have each evolved over time: capitalism towards a more liberal state, democratic socialism toward a pro-capitalist position than Serge could not have imagined, and Stalinism toward a much softer variant of Brezhnev-like sovietism.

There are forces that Serge underestimated though. Mostly because of his historical background. As the very partial list of people mentioned here should make clear, the ideological world within which Serge moved was that of continental Europe, of five great nations: Russia, Germany, France, Spain and Italy. Anglo-Saxon world is hardly present at all—especially absent is Britain. The Third World is non-existent. In a few dispersed remarks, Serge strangely failed to see the enormous revolutionary potential of Africa, India, China, Indonesia. His descriptions of Mexico, as he travels through the country, are worth reading for their glimpses of rural and urban life in the 1940s, pyramids and lost civilizations, but they are observations of a tourist. While his engagement with Europe is close and passionate, his engagement with Mexico is refracted only through the role that Mexico plays in European conflicts and particularly in the Spanish Civil War. There is a total dearth of political or social observations on Mexico itself.

I would like to finish with Serge’s observations on two fascists whom he personally knew at the time when they were communists: Jacques Doriot (“Zinoviev liked him”) and Nicola Bombacci. They were both killed in retribution at the end of the War. Bombacci was one of the fifteen executed together with Mussolini. Their transition from communism to fascism is explained by the need for restless activity, great organizational skills, and ambition. But there is one interesting, small ideological detail: both, Serge thinks, might have seen fascism within Marxist scheme as a ruse of history where decrepit capitalism adopts fascism as a way to save itself; yet fascism, by imposing a strong state rule over private sector, gradually transforms it, and creates an economy that can, in a future evolution, be readily taken over by workers. In such a bizarre way, fascism was, he believes, seen by the former communists, as a way to end capitalism.

PS. The editing of the book is close to catastrophic (the translation however is good and fluid). Dozens of people mentioned by Serge are unidentified; those who are, are so in minimalistic endnotes; many events alluded to in the Notebooks are left unexplained; the introduction is brief and not very helpful. Quite incredibly, the book lacks the name index. The publisher was clearly saving on money.

One of those fascinating lives from that bohemian/revolutionary period (like Jaroslav Haśek, author of Good Soldier Švejk). What many people don't know, don't remember, or pretend to ignore is that the fiercest and most articulate criticisms of the Soviet Union came from the left. I remember. Unfortunately there is no left left.

“But there is one interesting, small ideological detail: both, Serge thinks, might have seen fascism within Marxist scheme as a ruse of history where decrepit capitalism adopts fascism as a way to save itself; yet fascism, by imposing a strong state rule over private sector, gradually transforms it, and creates an economy that can, in a future evolution, be readily taken over by workers. In such a bizarre way, fascism was, he believes, seen by the former communists, as a way to end capitalism.”

Ok, let's do some History 101 in order for people reading this to not get too confused. Oversimplifying a lot, we have:

Marx's opus (not the personal stuff like letters and sketches, only the formally written to be published): scientific work, by now consolidated as absolute scientific truth (specially his magnum opus, Das Kapital). If you don't believe it, your loss - it remains true you believing it or not.

Marxism: people who claim to follow Marx's writings to any degree and found an ideology and/or doctrine which they claim to be based on Marx's works. Can vary widely in degrees of sophistication, erudition, and scientific precision. Anybody can claim to be a Marxist.

Marxianism: the alleged scientific and/or academic experts on Marx's opus. They are almost all invariably academics (i.e. scientists), employed as professors in universities, in which they dedicate their research and teach on Marx's theories. The scientific study of Marx.

Political doctrine: a manual of politics and administration of the State based on some principles, often theories and ideologies. After Marx, the scientific debate on socialism was deemed as over in Europe: Rosa Luxemburg, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trostky etc. considered themselves Marxists in the sense that they knew Marx was right, and sought to apply his theory to their respective realities in the political arena so as to obtain a certain goal (socialism). Their works were never intended to be elevated to the status of ideologies, let alone scientific theories. That they had just adds another archeological layer to the original question.

What we do with these definitions when studying History? Well, for starters, it shows ideas and ideologies never exist in a pure state: people think they have the same ideology, and/or claim to have this or that ideology, but they almost never have the exact same ideology, because that is virtually impossible. A Marxist may or may not have read Marx at all; some may have read just “Young Marx”, others just “Old Marx”. Most probably just read the Communist Manifesto (which is smart if your time is scarce, because the CM is a political program, therefore has immediate practical applications); a very small percentage may have read the first three chapters of book I of Das Kapital; an amount that can be counted on the fingers of two hands read the whole thing. Either way, someone may believe to be a Marxist just after a small contact with Marx's opus.

Hence, for example, Karl Popper - one of the founding fathers of Neoliberalism - was a communist. And the founder of Neoconservatism was a Trotskyite. Were they really ever “Marxists”? We'll never truly know, if this question is scientifically pertinent in the first place.

And this is a very common thing that permeates all of History, because it is in the nature of ideologies. For example, we know that, in the strict sense, the Roman Senators and emperor Marcus Aurelius were not true Stoics in the original sense, as Stoicism probably had a strong class critique element. It had to be sterilized before being canonized by the Roman elite. But did those senators and emperors really believe they were Stoics? They probably did. Deep down, ideologies are just that: instruments individual humans use and abuse and discard according to their day-to-day needs; there is no IP on ideology.

That's why we should be very careful when studying ideology in History: never take the term itself literally; never assume it was an organized and well-defined political movement; never assume they were uniform. But most importantly, never assume they have the reins of History: those are in the hands of economy.