Today [written in January 2019] I participated in a nice web-based program started by the Central Bank of Russia (it will be posted soon). An economist is being interviewed by another, and then the one who has been interviewed becomes in his/her turn the interviewer of yet a third one. My friend Shlomo Weber, the head of the New School of Economics interviewed me, and then I interviewed Professor Natalya Zubarevich, from the Lomonosov Moscow State University and a noted scholar of Russian regional economics.

Just a couple of days ago Natalia gave a very well-received talk at the Gaidar Forum in Moscow on (what one might call) “unhealthy convergence” of Russian regions. In fact, Natalia shows that most recently regional per capita GDPs have started a mild convergence, but that this is due first to low growth rate of most of them and the economy as a whole, and to the redistribution mechanism (mostly of the oil rent) between the regions. A healthy convergence, Natalia says, would be the one where economic activity, and especially small and medium size private businesses, were much more equally distributed across some ninety subjects of the Russian Federation. She also had very interesting insights into the excessive “verticalization” of economic power and decision-making in Russia, and the economic growth of Moscow (much faster than of any other part of Russia) driven by centralization of that power, and concentration of large state-owned or state-influenced enterprises as well as bureaucracy in Moscow.

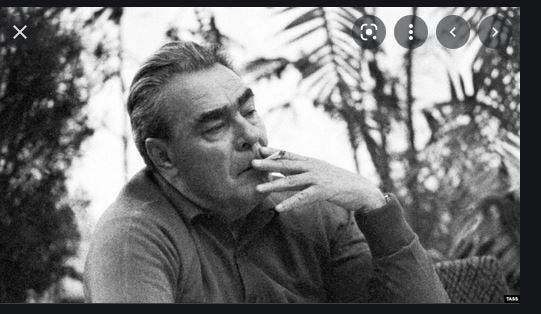

What most attracted my attention during Natalia’s presentation at the Gaidar Forum was her description of the current period of low growth rates in Russia as zastoi, or stagnation. Now, zastoi has a very special political meaning in Russian because it was a disparaging term used in the Gorbachev era, and by Gorbachev himself, to define the Brezhnevite period of declining growth rates, lack of development perspectives, unchanging bureaucracy, and general demoralization and malaise.

But I asked Natalia the following question. Looking over the past 150 years of Russian history (and I think it is hard to go further back), were not really the best periods for ordinary people exactly the periods of zastoi: incomes rose by little for sure, but the state repression was weak, there were no wars, and probably if you look at violent deaths per capita per year, the lowest number of people died precisely during the periods of zastoi. So perhaps that zastoi is not so bad.

Natalia said, “I know it: I lived through the Brezhnev period. Many people were demoralized; but I used it to study. I never read so many books and learned so much as then—you could do whatever you wanted because your actual job really did not matter much.” (Even art, as I saw in the Tretyakovska Gallery, although some of these paintings were never exhibited in the official museums, seems to have done well during the Brezhnevite zastoi. And as the recent film, which I have not seen, but read the reviews about, Leto, appears to indirectly argue as well.)

The best growth periods, as Natalia said, and as is generally accepted by economic historians were the 1950s up to about 1963-65, and then the period of the two first Putin’s terms. In both cases, the growth spurs came as a ratchet effect to the previous set of disasters: in the Khrushchev period, to the apocalypse of the Second World War, in the Putin period, as a reaction to the Great Depression under Yeltsin during the early transition.

So this then made us think a bit back into the past (say, going back to 1905) and put forward the following hypothesis: that Russian longer-term economic growth is cyclical. The cycle has three components. First a period of utter turbulence, disorder, war, and huge loss of income (and in many cases of life as well; period A), followed by a decade or so of efflorescence, recovery and growth (period B), and finally by the period of “calcification” of whatever (or whoever) that worked in that second period—thus producing the zastoi or stagnation (period C).

I do not know if this is something specific to the Russian economic history. It made me think of Naipaul’s observation on successful and unsuccessful countries. The history of the former consists of a number of challenges and setbacks indeed, but certain things are solved forever, and then new challenges appear. Take the United States: the Indian challenge and then the independence from Britain were not easy to overcome/acquire, but eventually, they were and they never came back; then the Civil War and the Emancipation; then the Great Society etc. But unsuccessful countries, according to Naipaul (and he had, I think, Argentina in mind) always stay within the circular history. The same or similar events keep on repeating themselves forever without any upward trend—and no single challenge is forever overcome. In each following cycle everything simply repeats itself.

The challenge for Russia today is to break this cycle.

This looks a lot like Gunderson and Holling's (2002) adaptive cycle hypothesis where complex systems (social, economic, ecological) pass through four phases: development, conservation, crisis, reorganization and so on ad infinitum. While not a big supporter of such a general hypothesis, you can see in its simplicity its persuasiveness.

У США была защита океанами, у Европы - Атлантическим океаном и Россией, у Китая - стеной, у России не было такой защиты. Это не оправдание моральной деградации, выраженной в эсхатологических и эвристических подменах деонтологического воспитания , но это специфическая причина отставания и путь направления помощи.