Reframing the world

I listened this morning to a brilliant talk by Danny Quah on what changes in the world during the past twenty years or so portend for the intellectual leadership of the world, or to be more specific, how the political and economic life should optimally be organized given the global changes in economic power that we are witnessing. In the beginning of his speech Danny defines the two tenets of the Western (or as he puts it, American) framing of an optimal society: economic freedom and democracy. This is the well-known paradigm of liberal capitalist democracy that, according to Fukuyama and later Acemoglu and Robinson, represents the end point of human evolution. Danny links it, rightly in my view, in addition to “American exceptionalism”, that is to the belief that America, by its own example, shows to the world how it should be organized, and that ultimately, the way the world will end up by being organized will be as a form of a “Greater America”.

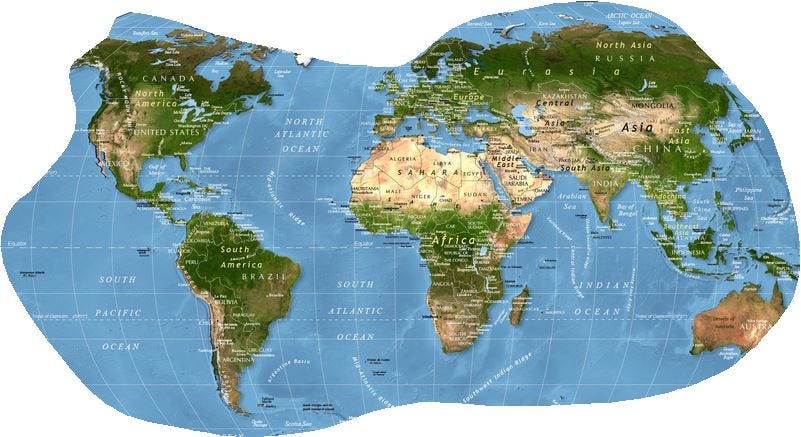

But then, Danny says, something has gone wrong with this approach. First, the economic and military dominance of the Western world is not nearly as overwhelming as it was one hundred years ago, or even fifty years ago. That dominance is being eroded by the growth of other parts of the world organized according to different principles, and obviously so by China. So if the performance of the liberal capitalist model is inferior to another model, then perhaps democratic liberal capitalism is not the best way to organize the mankind everywhere? Second, in responding to the challenges of globalization and the hollowing out of the domestic middle classes, a significant part of the Western public opinion shifts to populism, nationalism etc. all the forces that a successful liberal capitalist model should make sure remain marginal. But they are no longer so. Third, Danny raises the issue: should not our thinking about what is the best way to organize economic and political life be influenced not only by who is doing it most successfully but also by where the majority of the world population lives? It is not simply an arithmetical point. It comes from requiring that the modes of successful life that many people experience do have a greater empirical validity than the ways of successful life experienced by smaller groups of people.

All of this points, even if Danny does not say it so in his speech, to the Chinese experience as a “reframer” of the optimal organization of society. To redefine what best society is, is indeed a huge intellectual undertaking because if an entirely different paradigm of how to organize society becomes dominant, the paradigm built in the West over the past 300 years would be shunted aside and our view of what is a “good society” will undergo a revolution. We are talking here of nothing less than a major intellectual revolution, say similar to the move from paganism to Christianity in the West.

Danny however does not define this new framework. It could be that this is left for another speech or a book. But I do see some problems with the definition of a new framework. Let us take it as self-evident that the Chinese experience of the past half-century has been the most dramatic example of betterment of mankind ever. We should be able, in principle, to learn something from it: how to organize other societies to replicate the Chinese miracle. But there are problems. Unlike the Western success, following upon the Industrial Revolution, that was built through a combination of abstract thinking (about free will, property, freedom, role of religion etc.) and practical, if imperfect, application of these principles, the Chinese experience is entirely composed (or so it seems to me) of pragmatic moves without an overall intellectual blueprint. Such pragmatic experiences are difficult to transplant precisely because their success depends on local conditions and on finding the best solutions to very local problems. This extraordinarily success in solving local problems lacks a general “mode of solving the problems” that could be exported elsewhere. This is indeed a challenge that China has had in influencing the economic organization of the rest of the world for a while: inability to formulate general (abstract) principles that should guide other societies too.

In the political arena, the problem is perhaps even graver. There, in the Chinese model, the good political system means that a well-educated, knowledgeable and non-corrupt elite, selected in a reasonable equitable manner, should make important political decisions. (I am intentionally not saying “rule”.) Again, while that approach, applied in Singapore and China, had proven successful, it is difficult to see how it could be transplanted elsewhere. Even the most extractive and self-interested elite will claim to be knowledgeable and non-corrupt. The advantage of the Western democratic model is precisely its focus, not on the ultimate result (“good governance”) but on the process—essentially as in Schumpeter’s definition of democracy “a system where political parties fight for who will get more votes”. That system does not guarantee a good government, or a “clean” government, does not protect against nationalism, populism or nationalization of property. But it places its faith in the common sense or ability of people to learn from their mistakes, so that ultimately they will tend to choose good and reasonably competent governments to lead them.

Now, despite these problems of defining an alternative framework, Danny has in my view opened an extremely important issue which will be will us in the foreseeable future. If the most successful part of mankind is organized according to principles A, and our historical and cultural experience tells us that the best way to organize society is B, how long can this tension persist? Either we shall have to derive some general principles from A and apply them worldwide, or the societies currently applying A may move to taking over B themselves, or B might again become economically mst succesful. The one thing that cannot last forever is that we keep on believing that B is the best way to run societies while empirically the most successful societies are run according to A. Theory and practice will have to came closer. At some point

Thank you for your comment. I agree w/ most of you wrote and it is quite clear from "Capitalism, Alone" as well as from my work on global inequality (some of which will be uploaded tomorrow, and deals extensively w/ China). But where I disagree is that I think that China (despite its successes) does not have a simple model that can be easily sold elsewhere, neither in economics nor in politics. I think this is because the CHN model was created pragmatically, inductively, responding to specific conditions. Something so specific cannot be easily transplanted elsewhere. It ought to be "packaged" (if possible) in more general, abstract principles.

The argument is terribly flawed. Liberal democracies are - to quote Marx - ‚a democratic swindle‘. It is a game of distraction where the people have no real say in decision making. To state as in the article ‚it is not the end result but the process‘ is exactly that game of distraction bourgeois democracy has been playing all along. People are reduced to gullible voters while the real power relations are decided behind the scenes. The establishment tells you they have set up a system which they call parlamentiary democracy and which has been institutionalized.

So they say, pick one of us, a member of the democratic institutions, i.e. one of the establishment, because we are qualified and we will do the job for you. This creates the illusion of say in decision making through a representative, who always is one of the privileged classes, because otherwise, given the predominant power relations and the ownership structures, you could not make your way through the institutions. In fact it is something which is perfectly in line not just with what Hume has been stating, but with the principles of the founding fathers of America: Whoever owns the country should rule it.

In economical terms Adam Smith expressed this as the vile maxim of (the ruling class*) the masters of mankind: All for ourselves and nothing for other people.

Marx most strikingly subsumed all of that in the statement of the democratic swindle:

One side was the utilization of democratic forms as a cheap and versatile means of keeping the exploited masses from shaking the system, of providing the illusion of participation in the state while the economic sway of the ruling class ensured the real centers of power. This was the side of the “democratic swindle”.

The only real, but unfortunately short lived democracy ever existing was the Bolshevik set up of soviets (councils) which enabled direct voting and control of and through the people. Lenin was forced to reverse most of that under the military and economical pressure during the years of war communism. Direct democracy exerted by the masses is the only thing rulers and elites are afraid of. As long as you do have a class society you can play the distraction game. Just look at despicable identity politics which is pitting one group against the other just so people do not realize we are all in the same boat. Liberal fake democracy is a matter of avoiding class politics. It is a hoax and only serves power to preserve existing structures. It is an individualized society where people are not free - politically, socially and economically. The cheap substitute of so called free speech is powerless if no one will hear you. The vote has no weight, because you only can choose between different sides of the same coin. Western capitalist systems equate democracy and freedom with the available level of consumerism for individual preferences and choices. It is a pathetic buffoonery.