New Capitalism II: Compositional vs income inequality

Are all class-based societies unequal?

In my last Substack I discussed the concept of homoploutia. In brief, for those who do not feel like (re)reading my entire post, it is based on the empirical observation that in modern capitalist societies an increasing share of the rich are rich in two dimensions: they are among the best paid workers, and among the richest capitalists. I operationalize this idea by looking at the top after-tax income decile, top labor (wage) decile, and top capital (rents, dividends and interests) decile in some two-dozen countries. It turns out that almost one-third among the richest income-decile Americans are “homoploutic”, i.e. they are best-paid workers and richest capitalists. This makes for an elite of about 3% of Americans. That elite, as I discuss in the post, in Capitalism, Alone and in the forthcoming The Great Global Transformation is not similar at all to the vaunted professional middle class, or professional managerial class (PMC). It is ideologically strongly pro-capitalist and pro-private property because within their own persons they accomplish the fusion of capital and labor. Hence the elite strongly defends the rights of capital, low taxes on capital incomes and wealth, and everything else that goes with it. This neo-liberal ideological aspect of the new capitalist elite should not be neglected.

But the question can be asked: what happens if the contradiction between capital and labor income is transcended not only among the rich but along the entire income distribution? What happens if everybody has the same share of their income come from capital and labor? Say, the rich person receives $100 from labor and $50 from capital, the middle class person receives $40 from labor and $20 from capital, and a poor person receives $2 from labor and $1 from capital. What you notice here is that incomes are unequal but that their composition is the same. For each person, labor to capital income stands in the ratio of 2 to 1. A clear implication of compositional equality is that an increased share of income from capital that may occur as the result of the spread of artificial intelligence, will not affect overall inequality. If importance of capital income doubles, everybody’s income will increase by the same proportion, and the income ratios between our individuals will stay the same: instead of the distribution being (150, 60, 3), it will become (200, 80, 4). The relative income ratios remain unchanged at 2.5 to 1 for the top two guys, 50 to 1 for the top and bottom, and to 20 to 1 for the second and the third.

Around the time when I defined homoploutia, Marco Ranaldi, in his Ph D dissertation defended at the Paris School of Economics, grappled with precisely that question: how do we study compositional inequality? As my example makes clear compositional inequality is different from income inequality: we can have full compositional equality and yet a very high income inequality. To study this, Marco developed an entirely new methodological apparatus following closely the Gini methodology. Instead of having as an “objective” function equal income for all (as in Gini), Ranaldi put the objective function to be equal factoral shares for all, and calculated inequality as the sum of departures from such compositional equality. He defined an index, called IFC, (income factor composition index) that ranges from zero where everybody (as in my example above) has the same structure of income, to the value of 1 when income composition reaches its maximum, that is, top x percent of people have only capital income (until all capital income is “exhausted”) and the remaining 1-x people have only labor income.

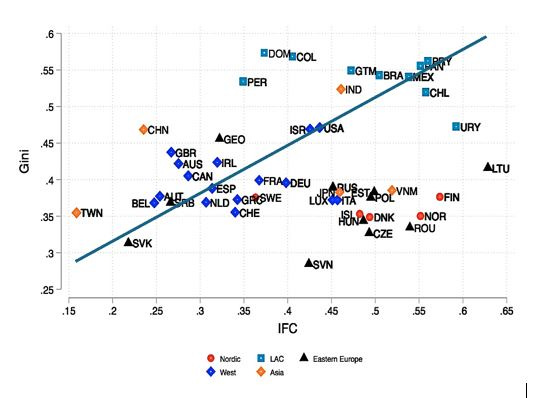

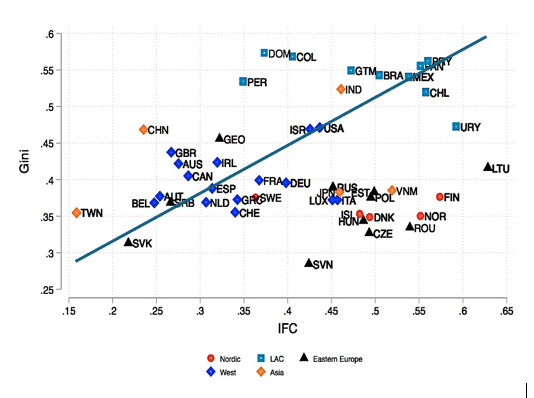

Ranaldi’s approach made it possible to study different capitalisms within a novel framework, utilizing two empirical observations: level of income inequality (say, Gini coefficient) and the extent of compositional inequality which proxies for a class-based society. We thus combine two important elements: sociological or political (class society) with economic (how unequal is it). In a joint paper, Marco Ranaldi and I, using micro data from Luxembourg Income Study, came up with the following graph.

Note: The graph shows Gini coefficient of augmented market income (wages, interest, dividends, rents, self-employment income plus pensions) on the vertical axis, and index of compositional inequality on the horizontal axis. Calculated from micro data from Luxembourg Income Study (LIS); period around 2020.

If one draws a straight line from the NE to the SW corner of the graph, one notices, not surprisingly, that income inequality tends to decrease as compositional inequality goes down. Consider Latin America, in the NE corner: Latin American countries are known for their high income inequality; it turns out that they also have very high compositional inequality, meaning that rich people tend to receive most of their income from capital, and the middle income and the poor from labor. Typical class-based societies, one would say. Indeed it seems “normal”, as in classical capitalism, to expect that the two inequalities would move together. Going further down the line, we get to the bulk of rich countries with middling levels of income inequality (Gini of around 35-40) and middling compositional inequality. Note that many of these countries, as we have seen in my previous post, have a homoploutic elite and that tends to dampen the index of compositional inequality. Finally, in the bottom left corner, we find low inequality countries (Gini of around 30-35) with a relatively low compositional inequality. Taiwan and Slovakia stand out by both. China, on the other hand, stands out by its relatively high income inequality, given its low compositional inequality. Can China be a precursor of a non-class-based yet high inequality society of the future?

So far, so good. But there are two important points to make. Note the anomaly in the bottom right corner: these are mostly Nordic countries (Finland, Iceland, Norway, Denmark) with low income inequality but high compositional inequality! Where does it come from? The answer is that it is driven mainly by income from private pensions that is treated (rightly) as capital income. So while many elderly people, who draw on their pension funds, have almost all their income derived from ownership, many working-age people receive the bulk of their income from labor. This makes for strong compositional inequality. (Note that today’s workers may be saving for future pensions by adding to their private pension funds, like people in the USA save through 401k, but they do not yet draw capital income from it.) We thus uncover a seeming anomaly: Nordic and Latin American countries are both compositionally unequal, but income inequality in the former group is low and in the latter high.

Further, look at the upper left corner: no country there. In another paper (on which I would later say more) Ranaldi calls it an important “non-result”. The fact seems to be that compositionally equal countries do not have high income inequality. Theoretically (as can be seen from my simple example above) nothing stops compositionally equal countries to have high inequality. In my example Gini was 46: I can make it arbitrarily high by having the top person’s income become $1 million from labor and $500,000 from capital, the second person’s income $100,000 from labor and $50,000 from capital and the third person $2 from labor and $1 from capital. Ranaldi’s IFC index is still zero, but Gini will now be a super high 61.

Yet in real life, it seems that low compositional and low income inequality go together. This then opens the doors, as our paper indeed does, to some fruitful discussion of various types of modern capitalism (remember China vs. Taiwan contrast mentioned above). We can move from the by-now tedious exegesis of the so-called “varieties of capitalism” where most of the action is the debate on the parental leave in Norway vs the US, that is, from a literature that seemed to have gone AWOL during the past thirty years while distinct forms of capitalism appeared in Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, Kenya, Russia, Thailand etc. etc. to an empirically based classification and analysis of various capitalisms—a classification moreover that unites political and economic elements.

This is not all. Marco Ranaldi, in two recent papers, one in Review of Political Economy (May 2025) and another as PIAS Working Paper, tries to formulate the guidelines for an analytic and even cognitive framework where the issue of compositional inequality (that is, capital vs labor) would be at the center-stage. He asks what a society of much greater compositional equality might imply for class contradictions, universal basic income, spread of artificial intelligence, climate change, even philosophy of different modes of production. I would suggest to read his papers if you are interested in these issues. (And, frankly, I think you should be.)

In my next blog, I will complete the trilogy on modern capitalism and new analytic ways to comprehend it by discussing….the omitted factor of production: capital! I will look at the importance and distribution of income from ownership of assets, a great determinant of overall income inequality. The determinant moreover that was forgotten by many economists in the post-Kuznetsian period, fearful that they might seem too “socialistic” if they were to discuss capital’s contribution to inequality. This was the case until many were woken up from their somnambulance by Piketty’s block-buster. We should go further along that road.

This is very interesting to me as a sociologist who studied real property and has been working on an alternative to neoliberalism.

It should be noted that the pension systems in the Nordic countries are legally mandated, with a quite narrow strategic latitude as defined in legislation. The future pensioners do not personally participate in investment decisions to anything like the extent that characterizes the US system under 401(k).

In fact, at least in Finland, the assets of the nominally private pension funds have traditionally been counted as assets of the public sector when calculating the public debt ratio, etc. The pension funds are treated as something not very different from a sovereign wealth fund.