Limits to autocracy

Review of Charles Hucker’s “The Censorial System of Ming China”

Charles Hucker’s book was published in 1966. Charles Hucker was one of the foremost American scholars of Chinese literature and history. The objective of “The censorial system of Ming China” was to empirically review and analyze the role of the censors and the censorial system during two different periods of Ming dynasty: the first 1424-34, the one of relative domestic tranquility, and the second 1620-27 when, almost at the end of the Mings, Northern borders were assaulted by the Manchus and domestic politics were in turmoil. As Hucker writes, the archival documents during the Ming era are enormous, and as a solution to make a study of the censorial system practicable Hucker selected two different periods—to see if the system and its actors behaved differently under different conditions.

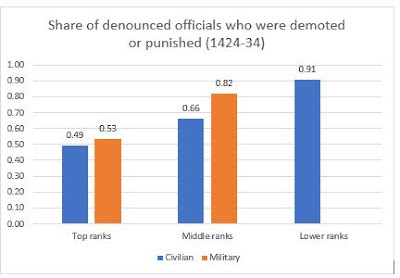

What is the censorial system? It is a part of civil service (with officials, in principle, competitively chosen although—interestingly—with an “affirmative action” in favor of candidates from Northern and Western provinces) whose role is to surveil the realm and check how government policies are implemented, to control lower-level administrators who are in charge of applying such polices, but also to remonstrate with the Emperor and the “inner court” when some policies, according to the censors, are wrong or unimplementable. The censors’ role even includes possible rebuke of emperors if they decide to ignore sensible censorial recommendations (“the speaking [to the Emperor] officials”). Censors are thus both an arm of government and its controllers. In modern systems like the American, their role could be seen to combine that of the Government Accountability Office with the court system. The censors in effect had a judiciary role because they were empowered, without further check with top authorities, to impeach, demote or punish lower level officials whom they found incompetent, venal or immoral (p. 244). One of striking parts of Hucker’s book is the amount of extant empirical evidence regarding censors’ decisions. For example, at least 261 civilian and 398 military officials were denounced during the ten-year period 1424-34. Among them at least 67 were nobles and category 1 (highest rank) officials. Despite the fact that demotion and punishment was more likely to be meted out to lower ranks (see the graph below), the top officials were not exempt from denunciation and about one-half of them were demoted or otherwise punished.

Source: Calculated from Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix.

I do not think that a similar type of organization existed in centralized European autocratic systems. In Byzantium, government officials applied policies, but there was no systematic government agency (short of government spies) to check on them. Much less on the Emperor. The same is true for Imperial Russia. The French intendants de finances had strong powers over pays d’elections devolved from the Center, viz. the up-to-down power, but they had no power to stay the execution of King’s orders nor to check royal authority.

The censorial system was one of two elements that during the Ming dynasty (and probably throughout most of China’s imperial history) were destined to temper, limit and mollify autocracy. The first was education of emperors, teaching them Confucian doctrine of imperial virtue and responsibility towards people “([the emperors] had continually to listen to the lectures of moralistic Confucian scholars who were probably dour and seldom entertaining” (p. 43)). The second check on imperial power was the censorial system which owes (as Hucker writes) much more to the Legalist tradition than to Confucianism.

It is thus most interesting to see how effective were censors in opposing the emperor more than how effective they were in ensuring that the central policies were implemented. As one would expect, and as Hucker in the last chapter very nicely summarizes, the results were contingent on many factors: with better emperors, more conscientious of their duties and less willful, the censors did influence many decisions, whether positively by proposing certain policies, or negatively, by stopping wrong decisions. This was more the case in the first period of relative peace and “better” rulers. But even then, more impetuous emperors would at times get angry with top censors, demote them or even imprison them, often only to release and promote them later. The number of cases of censorial see-saws discussed by Hucker is so immense, and varied (censors who were sent to their provinces, those punished with loss of several years of salaries, those kept in semi-exile for a decade or more, only to be recalled when a different faction became ascendant at the Court or the emperor changed his mind) that the modern-era three-time purge of Deng Xiaoping appears like a rather unextraordinary fate.

During the latter Ming period the situation darkened. Political factionalization become much more severe as the external situation of the empire became more precarious and as the emperors were weaker, lazier and less competent. This allowed, in the most famous case, the silent coup of Wei Chung-hsien, the chief eunuch who was the head of the Eastern Depot (the secret police), to usurp imperial functions, install own puppets in the government administration, and then to punish the censors who tried to warn the emperor of inequitable taxation, promotion of corrupt individuals, and Wei’s budding cult of personality. With Wei firmly in charge of dynastic policies, he unleashed a rule of terror that decimated the censorial corps. Many positions remained unfilled for years, and censors brave enough to challenge Wei were sent to languish in prisons or were beaten to death or executed (often by strangulation). According to one calculation, 365 were punished or driven out of service, more than 20 of them executed (p. 271). As for ordinary people, the Ming History says, “Those who were murdered are beyond calculation; on the streets men used only their eyes” (p. 173).

To every student of history, this usurpation of rulers’ absolute power by the head of secret police comes as no huge surprise: one can see in it Sejanus gradually undermining Tiberius’ authority as the latter spent most of his time at Capri, or Beria slowly and slily accumulating more power for himself and NKVD, or finally even in Lin Biao planning to overthrow Mao. In all these cases, as indeed in Wei’s too, the attempt failed. A few upright and undaunted censors still remained, and in an extraordinary passionate and forthright memorandum quoted in extrenso by Hucker, one of them warned the emperor of Wei’s twenty-four "great crimes", some of which went directly against the emperor and his progeny and set the stage for the substitution of the emperor by Wei or his puppets. Such insolence eventually led to Wei’s downfall.

Therefore even in the tumultuous latter-Ming period, censorial check-and-balances continued to function, however unevenly or haltingly.

One obviously thinks whether the current anti-corruption campaign and the role of CPC’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection may mimic the role played by the censorial system. Hucker briefly mentions the influence of the censorial system both on Taiwan (the Control Yuan, one of the five yuans) and the People’s Republic. Today’s CPC’s Central Commission also has the right to investigate officials, to implement the rules of behavior but cannot by itself punish officials. They have to be brought to court. Also, it is unclear to what extent the Commission might investigate top officials even if its activities have moved to the levels that until recently were thought “untouchable”, indicting one member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, a vice-chair of the Central Military Commission, and at least (2018 data) 20 out of 205 members of the Central Committee. So even the “tigers” were no longer beyond the reach. However, it is likely that the authorization to go after a given “tiger” must still come from the top, i.e., the Commission is not fully autonomous in letting the cases lead it wherever they do. One however does not get the impression from Hucker’s book that, in a more serene atmosphere of the early Ming, the censors feared too much to go after their corrupt colleagues or eunuchs, their permanent nemesis. But whether the “bad elements” would be punished depended, then as now, on the correlation of forces at the top. Checks and balances worked—at times.