Disciplining workers in a workers’ state

When I reviewed yesterday Fritz Bartel’s excellent new book “The Triumph of Broken Promises” where he describes how governments in both the West and the East in the late 1970s and early 1980s had to break tacit promises (of economic growth and welfare state) with their citizens, he speaks of “disciplining labor.” In a capitalist context, it is clear what it means: reduce the power of trade unions, make the labor market more flexible (i.e. firing easier), reduce the duration and amount of unemployment benefits etc. Almost everyone understands it.

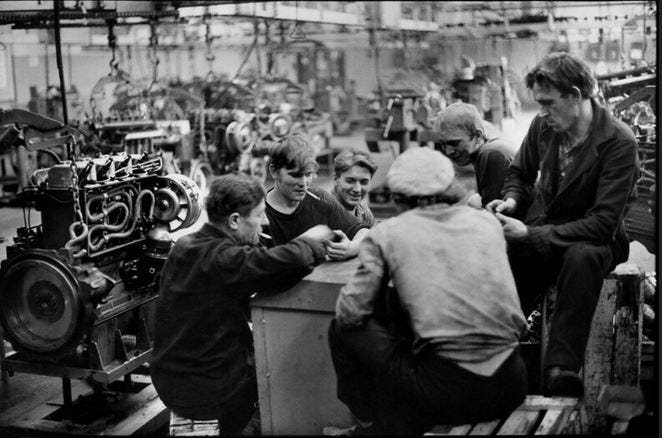

But some people wrote to me: they did not understand what “disciplining labor” meant in the East European (and probably Soviet) context in those years. To understand what it meant one has to start with the position of labor in socialist societies. In those societies, and in those years (because it was different under high Stalinism), workers were seen as the “privileged” class in theory. While they were not high in income distribution, they benefited from many egalitarian policies, and it is them, and their position, that provided the legitimacy to the communist party rule. Since that rule could not legitimated through elections, it had to be legitimated through the claim that it ensured the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, i.e., made workers, rather than capitalists, the ruling class. Obviously, they were not the ruling class in truth: party and government bureaucracy were, but the ideological claim of “the dictatorship of the proletariat” could not be openly ignored and it meant that a special social contract did exist between the powers-that-be and the working class.

The contract included the following items: (1) low intensity of work effort, (2) guaranteed employment, (3) low wage differences between skilled and unskilled workers, (4) less hierarchical plant-level relations than under capitalism, (5) social benefits linked to job.

The most important thing to realize is that work effort was much less, and the number of hours of effective work probably even less than in an equivalent capitalist-run firm. There were several reasons for it. Socialist enterprises were organized much less efficiently. There were no real owners who cared about profitability and in consequence they did not either care if labor was employed eight hours per day or four. On top of that, the overall system was less efficient: so often raw materials would not show on time and there would be no work to do. Then, there was surplus labor within companies, hired just in case they needed it to fulfill the quota (or, as in Yugoslavia, which was not a planned economy, just in order to hire family and friends). Companies were encouraged to increase hirings because local politicians were afraid of unemployment in their area and under their watch. They wanted companies to hire as many people as possible regardless of whether it made economic sense or not (the soft budget constraint will somehow mop all of this up: somebody else will pay). Finally, hours and hours were lost in political meetings, or as in Yugoslavia, in interminable discussions of workers’ assembly or workers’ councils.

All of these things combined meant for an individual worker that he or she effectively worked much less than in a corresponding capitalist firm: the intensity of work was less, the duration of work was less, the idling was much greater. Worker’s shop-floor position was stronger than in an equivalent capitalist firm because it was almost impossible to fire them. So he/she was both more powerful and worked less.

Comes the need for reform. “Breaking promises” under socialism meant principally disciplining labor along the three dimensions: make them work harder, reduce their shop-floor powers, and allow (timidly) for possibility of firing. As a careful reader might have noticed, disciplining labor had mostly to do with “internal” elements of the shop-floor organization, and establishment of stricter rules and hierarchy, not with the usual “external” elements as in capitalism (amount of unemployment benefit etc.).

I remember observing clearly these differences during the years when, to complement my student income, I worked with Yugoslav trade unions. They had very close relations with French Trade Unions (CFDT in particular) and I knew them well. When the French Trade Unions would visit Yugoslavia, they would be taken to the management of the company and to the plant-floor to chat with workers. When Yugoslav trade unions went to France, they would meet in trade union offices (very nice, by the way), but they would never meet the management (obviously the management would ignore us), nor would they ever be allowed to the shop-floor. The internal organization of work was entirely the “province” of capitalists and managers. Of course, unions may be consulted, or could strike, but the rules of work organization, the pace of work, the hierarchy within the company were not the object (or were seldom the object) of negotiations.

It is that very hierarchical work organization that technocrats, or reformers, in socialism wanted to establish so that the system would be more efficient. Consequently, they had to fight against the acquired rights of workers. This was ideologically difficult because workers were the “ruling class”. If they are the ruling class, how—and for what purpose—can you force them to work harder, be less consulted, and even face unemployment?

This was the perennial battle between technocrats, often company directors, and the working class. Whenever crisis would hit, technocrats would gain the upper hand. They would make temporary inroads, but would be thwarted and pushed back by a coalition of bureaucrats in the party and workers. It was a battle that was for ideological reasons impossible to win by technocrats. “Disciplining labor” was thus much more difficult in Eastern Europe in the 1970s that in the West, and especially so, in the United States, where the power of labor (and the ideology legitimating that power) was always weak.

It is way more complex than that.

The argument that socialism simply is an inferior mode of production doesn't explain why the USSR caught up technologically during the Lenin-Stalin era (just 29 years), and why, to this day, the USA considers communism by far the greatest existential threat to capitalism and, by extension, to itself. It also doesn't explain why, e.g. Russia is still a formidable enemy to the West, even though being merely a Third World country.

Soviet factories were not inefficient: the material arrived in time, stuff was produced in time etc. etc. The problem was how the CPSU did the calculations to establish the goals after post-Stalin: the workers and factory managers achieved the goals, but the goals were wrong - at least in the greater scheme of things, because basic necessities (food, shelter, healthcare, education) were satisfied.

The backwardness of the Soviet factory is also a myth. As mentioned before, the USSR quickly caught up and then surpassed the West in some areas during Lenin-Stalin-Krushchev. During WWII, the USSR surpassed Nazi Germany, arising from the conflict as the world's most powerful army and air force. During Krushchev, it pioneered space exploration. Innovation continued to thrive until the very end and beyond in the military sector (the Russian Federation is leader in many areas, such as missile, submarines, electronic warfare, etc. etc.).

The reason 9 out of 10 Soviet people in the street say their factories were inferior to the West lies in the fact that, for the common citizen, what matters is light industry, not heavy industry: their perception of technological advancement is fetishized in the durable consumer goods such as cars, phones, ovens, refrigerators, portable computers, fashion clothing, housing accessories and customization etc. In this sector there is no doubt, the USSR was inferior to the First World capitalist nations in all aspects: in fact, this inferiority was the main reason, if not the only reason, for Gorbachev's failed reforms. Just to give you the magnitude of the seriousness the communists treat this issue: that is the reason the CPC lets the private sector/free market to operate in China. So far, the socialists (Marxist-Leninists) haven't found a purely socialist solution to satisfy those needs; the answer is probably the still low levels of development of the productive forces, as socialism is still a very young system (just completed 105 years of existence).

I recommend the reading of Brazilian researcher Angelo Segrillo's PhD thesis on the fall of the USSR for a more complete explanation. To grossly oversimplify, the USSR wasn't able to jump to the Third Industrial Revolution, i.e. transit from Fordism to Toyotism because that would require a too deep and traumatic change of the system. In a context of direct competition with capitalism, it was unacceptable for the USSR to exist as a second-rate power, so it had to force its hand and, when it failed, it collapsed.

Note that the Soviet collapse was purely political. Its economy, albeit stagnated, was fine by historical standards. It could have existed as a stagnated country indefinitely if not for the pressure of the Cold War (other lesser socialist nations such as Cuba and North Korea still exist to this day). The USSR also was never militarily defeated, so that factor must be immediately ruled out (this factor still causes the USA much problem, as the Russian Federation still has a native elite that has a consciousness of sovereignty, best illustrated by the episode of the humiliation of the IMF of 1998). Besides, the USSR left a surviving heir: China.

Obviously, very good example how the labour disciplin worked in the Eastern countries and in southern Europe. During the 70's labour unions have been differently organised in different regions and countries of Europe. One exceptional example is Nordic countries, particularly Sweden, where trade unions had very good relationship with Employers association, difficult labour market problems always resolved with common consensus approach, never with ruling governments intervention. Just a exempel of very unique Western trade unions relationship with Employers that was very effective for almost three decades untill strong neo-liberism influences in political ecosystems in Nordic and in particular Sweden.