A pedagogical tax

Why the rich should be uber-taxed

I have not discussed the proposed Zucman tax so far. I am not in general a huge fan of trying to solve every income or wealth inequality problem by taxation. But two recent developments have led me to think again and support strongly the Zucman tax and perhaps to argue to make it even tougher.

The rationale of the tax is not that it would significantly dent the wealth of the rich; nor would it collect huge revenues.

But it would convey a message. It is a tax against greed. It is a pedagogical tax.

What are the two recent events that made me think again?

The first is the review by Andrea Capussela of my Great Global Transformation. It re-brought my attention on the last chapter of my book entitled “Nationalism, greed and property”. Andrea wrote quite a lot on it, and expanded the discussion further. (Andrea’s review’s title is “Impeccable, and unacceptable portrait of our world”. I suggest that you read it.) Interestingly, this is also the only part of the book discussed by Martin Wolf in his brief review of the book in The Financial Times.

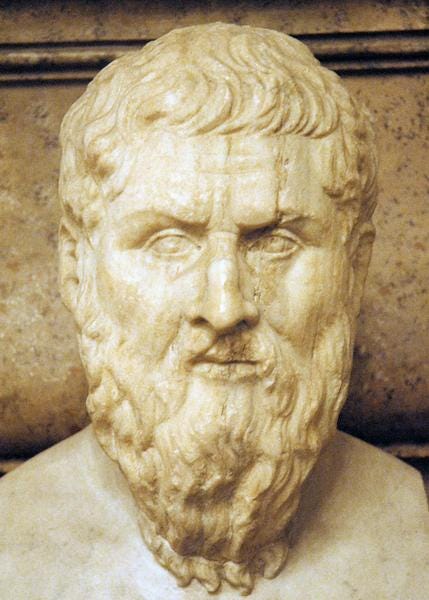

I have, to some extent, even forgotten about it because my book (or 95% of it) is about other things. The last chapter is only five or six pages long. Greed (pleonexia) plays a key role there though. (Pleonexia is also discussed beautifully in David Lay Williams’ recent book The Greatest of all Plagues). Pleonexia is a greed without any upper bound. It is not based on intrinsic pleasure provided by consumption of goods and services. Its utility comes from elsewhere. It is extrinsic: admiration of the others. Here is what I wrote in The Great Global Transformation:

Things possess an indirect utility because they convey to the others the image of wealth and power of the owner. Since the image of wealth and power is not bounded from above– that is, does not have any physical limits (unlike, for example, food or clothing one can consume over a given period of time) – it becomes what is commonly called greed, the pleonexia of Plato and the Greeks, the all-consuming and never assuageable greed. Greed is extrinsic. It cannot be ascertained or judged from within, in the sense that one cannot objectively claim that the increase in the number of commodities owned above a certain limit does not bring additional utility. The utility it brings comes from an external spectator who, by being made aware or acknowledging our ownership of things, validates it, confirms that they are useful to us, and makes us want to have more so that the validation may be even stronger. Ubiquitous use of smartphones to take photos of the most trivial activities or events in one’s life fulfils that function: it commodifies time, and that new commodity acquires its value only extrinsically, when it is shown to others. Taking pictures of our own lunches or walks in the woods and keeping them for ourselves is wasteful. It brings nothing, or almost nothing, in addition to the potential pleasure one gets from the activity itself. But sharing it with others brings the recognition of either one’s wealth or, perhaps more importantly, of one’s happiness. Having one’s happiness confirmed by others is one of the features of greed. Pleasure is no longer contained in the activity or good itself, but in the appreciation by others of the happiness that the activity or the good are supposed to have brought to us. Matters can go even further: activities that bring no utility, or that are even chores, but can be presented as happiness, obtain their value precisely from that presentation, and not from any intrinsic quality. I may dread or be extremely bored by listening to classical music, but if I can send a picture that shows me attending an important or expensive performance (and ostensibly being happy even when feeling miserable), the utility that comes from the conviction that others see me as happy will be sufficiently strong to overwhelm my boredom during the performance itself. Greed is the ‘motor’ that drives our obsession with property since its acquisition is seen to be the ultimate objective – not only because of the hedonistic pleasure it gives, but because it shows the worth of an individual. Greed is, as Marx defined it, ‘abstract hedonism’.

The anti-greed pedagogical tax would, by cutting wealth of the inordinately rich, just by a little, send the message that society is not wholly oblivious of, or indifferent to, extreme greed, and to power and vanity that accompany such wealth, and make its possessors objects of (misplaced) adoration.

And provide them with a feeling of impunity.

Here then comes the second event which made me think again: the Epstein affair. The impunity with which the wealthy have behaved calls for some (however feeble) social constraint. Zucman tax would be one such modest constraint.

On top of it, I thought of a social credit system for all billionaires. If you do certain things well, you will be taxed less; if you do awful things (even if they are seemingly legal), your tax will be increased.

Social credit system would be an effective way to subject the behavior of the enormously wealthy to social scrutiny. There would no longer be meaningless Davos declarations that they “pledge” their fortune to charitable causes and similar fake and unimplementable plans. Did not Mark Zuckerberg give away 99 percent of his wealth? Had we ever heard of that “pledge” after the day it was made and reported by the media?

Here, social credit system would be real. Behave with a minimum of decency, or be taxed. It would be a pedagogical tool. Call it “the anti-Epstein social credit system”.

In this age and time the juxtaposition of benevolent greed-limiting taxation for the betterment of mankind and psychopaths like Epstein, Gates and who knows, is intellectually charming and - sorry to put it bluntly - incredibly naive.

Here is a related idea that seems to aim for the same outcome Mr. Milanovic is proposing (https://neofund.sk/node/16). It works somewhat in reverse: instead of raising or establishing new taxes and creating a social credit score to enforce compliance, it focuses on the power of the score itself — its public recognition — to motivate individuals to transfer their wealth voluntarily. It may seem far-fetched to expect people to exchange wealth for a signal, but this behavior is everywhere once one looks closely. The same score points should also be possible to earn through volunteer work and philanthropic contributions. Philanthropy in this context is discussed in Michael Spence’s proposal: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/wealthy-support-for-public-goods-through-philanthropy-by-michael-spence-2024-07